Are the Polish Tatras worth visiting? What is there to do in Zakopane? Read on to find out.

I first came to the Polish Tatra village of Zakopane in 1971, when my father drove us from England to Poland for a holiday. I remember the wooden buildings that lined the streets, and the time my father drank from a mountain stream that gave him a severe stomach upset; grey-faced, he lay on the hotel bed while my mother fretted that we’d miss the Ostende ferry back to England. But the image that clung most tightly to my memory was of a mountain peak looming over the town.

How fitting, then, that the highlight of my return 50+ years later was to stand alongside the iron cross on the summit of that very peak: Giewont. Not the highest (at 1894m) but an icon of Zakopane and a well-known profile of the Polish Tatras.

The Tatras, part of the Carpathians, symbolised Poland before it even became the nation we know today. And when Poland became a state after WW1, Zakopane and the Tatras continued to play a role in the development of Polish nationhood.

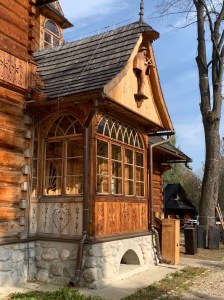

At the same time as architectural styles inspired by picturesque rusticity were developing across Europe (eg Queen Anne in England), the Zakopane style inspired buildings across the former Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia, and this is brought to life in the Museum of Zakopane Styles.

And the museum solved a puzzle for me. Its jutting veranda, with decorative wooden window frame, was a feature I’d noticed whilst travelling in Western Ukraine. A simple version even graced the old home of my family, built during the 1940s in a Ukrainian village within sight of the Carpathians. Back then I’d become fascinated by what seemed to be a local Ukrainian style. Now I know it’s typical of Zakopane rustic architecture. It must have become popular in Ukraine when those lands were part of Galicia.

Zakopane is a ski resort, but it’s also blessed with a grid of stone-paved valley trails leading south into the Tatras, crossed horizontally by other paved tracks. And at the top of all this is the ridge separating Poland from Slovakia.

The Kasprovy Wierch cable car gives easy access to the border ridge, where you can rest with your feet in two countries:

From the top of the cable car there there’s a choice of walks including a steep descent to the Czarny Staw Gąsienicowy lake, or one of many trails back down to Zakopane:

Like most people, I chose to walk up Giewont the hard way, from Zakopane: an ascent of 1,000m along the red trail. Halfway through the hike, the summit peak still looked impossibly far. And you can’t avoid some scrambling on the final summit pyramid, with heavy chains fixed to the stretches of smooth rock. A one-way system is in place, meaning summiteers ascend the eastern side and descend the western flank. At peak times hikers must queue to avoid potentially dangerous overcrowding on the summit.

And Zakopane itself? Modern buildings overshadow the traditional timber structures along the main street, where families sit on sheepskin-clad benches outside restaurants, entertained by a busking (Romany?) family whose enthusiasm and gyrating makes up for singing ability. In mid-October’s off-season the town was tolerably busy, but I do wonder how it copes with the crowds during the main summer hiking and winter ski seasons.

The Bazatatry website is a good source of information and accommodation for Zakopane.

Download my ebook ‘Travels in a Young Country’ (FREE from Apple, Kobo, B&N and some Amazon stores). All links are here: https://books2read.com/YoungCountry

Pingback: Interrailing 2022: ten tips – Michelle Lawson