In May 2023 I travelled from Lithuania to Croatia by train. It’s an epic route from northern to southern Europe and I used an Interrail/Eurail Global pass. How did that turn out? Well, it spawned an article on how not to plan an Interrail trip. It’s all explained in my article on the Go Nomad travel website.

For now, let’s forget the whole rail pass thing and look at the trip from Lithuania to Croatia by train. I’ve included details of accommodation but only those I’d re-book and recommend. These are affiliate links that may grant me a small commission if you book through the links, at no cost to you.

Exploring Vilnius and Kaunas

Arriving in Vilnius, the UNESCO-protected old town had a lively ambience that felt far from the dense crowds plaguing many other European cities on the weekend-break circuit. My bed was in the heart of the UNESCO-protected old town, a former monastery cell in the Domus Maria hotel.

It was a short rail trip to Kaunas, Lithuania’s second city. Once again, it was a novelty to walk around a city without weaving through crowds of tourists. I spent a peaceful night in the Best Western Santakos hotel, close to the old town.

Lithuania to Poland on the new Rail Baltica connection

The new international connection from Kaunas to Warsaw took seven hours, including a change of trains at the border at Mockva. Then add an hour to account for Lithuania being an hour in front of Poland.

Either side of the Tatra Mountains

Trains from Warsaw via Krakow sped me to Zakopane, Poland’s most popular mountain resort. There was so much snow that people were still skiing on the upper slopes, so I followed a line of hikers up, anxious that the increasing snow cover would make it difficult to get back down without crampons. But most other people were clad like me, in normal hiking boots, apart from the man wearing open sandals.

My destination was the Gąsienicowy meadows, a familiar image that graces Zakopane’s postcards, hiking routes and tourist websites. I was keen to stand among those green meadows dotted with pink wildflowers and cute wooden cabins, with a jagged grey mountain backdrop. But the lingering snow left it an unrecognisable monochrome with patches of rotting brown foliage. Even the peaks were smothered in thick cloud. Only hours later did the mountains emerge, when I rode the funicular up the other side of the valley.

This time I stayed in the Hotel Logos, which I’d recommend as it’s in a peaceful location but a mere 5 minute walk across the park to the main streets.

Exploring Slovakia by train

Avoiding a 2-day roundabout train route, I took the bus to the southern Slovakian side, spending a few days riding the electric trains running across the southern Tatra slopes. Then most of a day was spent riding four trains north-east to where Slovakia borders Poland and Ukraine. The first hours followed the scenic Hornád river, then a long wait at spooky Prešov station. Outside was a coffee and falafel stall, where the Middle Eastern owner crisped the falafel and asked about the latte. “It’s a new machine, used for the first time today. I bought the best I could,” he said. In the time it took to cook and eat the falafel, I was his only customer.

Bardejov’s UNESCO World Heritage square was so cold I layered up with almost every item of clothing in the backpack. I stayed at the Bardejov Kulturne Centrum, right in the main square and with prices from the last century.

Hungary, where everyone can once again feel at home

In Budapest the castle district was horribly crowded and the cafes all had queues. But few bothered to walk beyond the main tourist epicentre, perhaps put off by the enormous building site of the National Hauszmann Program. This extensive project is restoring Buda Castle to its previous glory after decades of post-war neglect. Hoardings tell how the current government is finally making up for the Communist indifference.

But it’s not just about architecture. It’s a project to symbolise Hungarian national identity, “to conjure up a place in the centre of the capital where everyone can once again feel at home”. The aim is to “return the castle to Hungarian people”. That hardly makes sense when the castle district is swarming with foreign tourists.

Hungary’s politics are increasingly nationalistic and authoritarian thanks to Prime Minister Orban. The previous day a former journalist told me how he’d left the job as it no longer involved writing news – “just propaganda”. Locals have replied to the official anti-Nazi war memorial (an eagle) with reminders that Hungary wasn’t always on the right side of history as far as the Jewish population was concerned.

From Lake Balaton to Croatia

The international train from Budapest to Zagreb followed the eastern shore of Lake Balaton, stopping at tiny stations and roadside halts over the six hours.

Zagreb was dark and rainy. Graffiti at the end of the station underpass greeted me with “God help us”. Ominous or what? Then my expectations were confounded as the station hall was filled with an enormous bookstall, still open at 10pm. A city that takes reading seriously!

The Hotel Central was no-frills but extremely convenient for a late arrival, being close to the station.

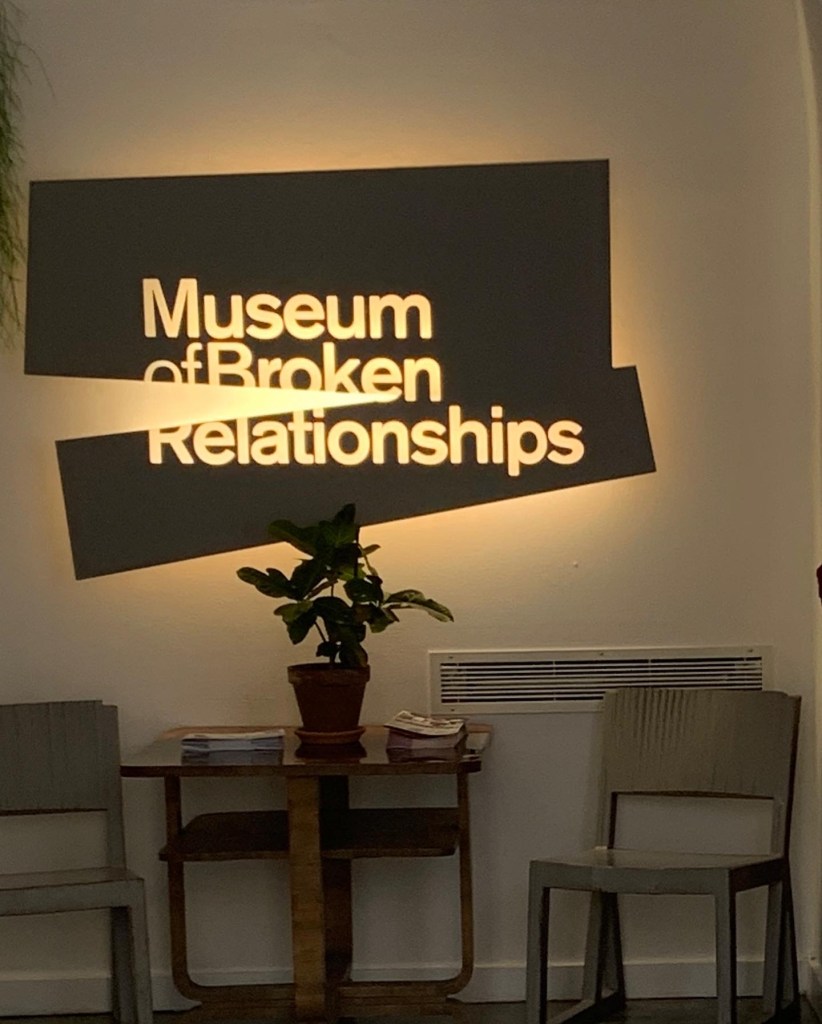

A morning in Zagreb confirmed it was an attractive city with narrow backstreets running through the old town, although churches were still closed due to earthquake damage. There’s an intriguing and poignant Museum of Broken relationships that’s exactly what it says.

The final train, to Split, was basic with no apparent refreshments, although beers appeared now and then from a secret stash. The isolated high land we crossed was spectacular, framed by a snow-capped grey mountain wall. We were running along the single-track Lika line, a battleground in the Homeland war of the 1990s, and some of the stations were collapsed shells. At one point my mobile thought I was in Bosnia. It was the most spectacular and memorable trip of the entire journey.

Swinging in Dalmatia

After a morning weaving through zombie-like cruise passengers around Split, I escaped to Trogir, yet another UNESCO town. Trogir sits on an island, built on Greek and Roman foundations with Venetian influences. History’s all around, from the bench constructed from ancient columns, to the photographs of 32 locals who died in the recent war between 1991-95 (go through the door below the clock tower in the main square).

The bus south followed a serpentine coastal road towards Dubrovnik, my final destination. But before hitting the crowds in Dubrovnik I needed to rest and gather my wits.

The fishing village of Gradac was a perfect choice as it lies halfway between Split and Dubrovnik. Even better, it barely features on tourist itineraries. And Danijela’s Apartment Like Home was just perfect for a woman travelling solo.

The price of ice cream is a good indicator of the level of commercialisation. At 1.50 euros per scoop, Gradac welcomes its visitors but doesn’t lean towards pretentiousness. Within an hour of arriving I’d already made plans to return. For longer.

Gradac has a swing on the beach. Instagrammers and wedding couples no doubt love the swing but fortunately they never made an appearance. That left me to swing morning, afternoon and night until it was time to leave.

This was an epic trip, no doubt, via some of Europe’s great cities. But I’ll never forget discovering a place that’s not even mentioned in the Lonely Planet guide. Evenings were the best, swinging myself back to my childhood, accompanied by the lights of the shoreline and the blaze of orange from the church above the tiny harbour.